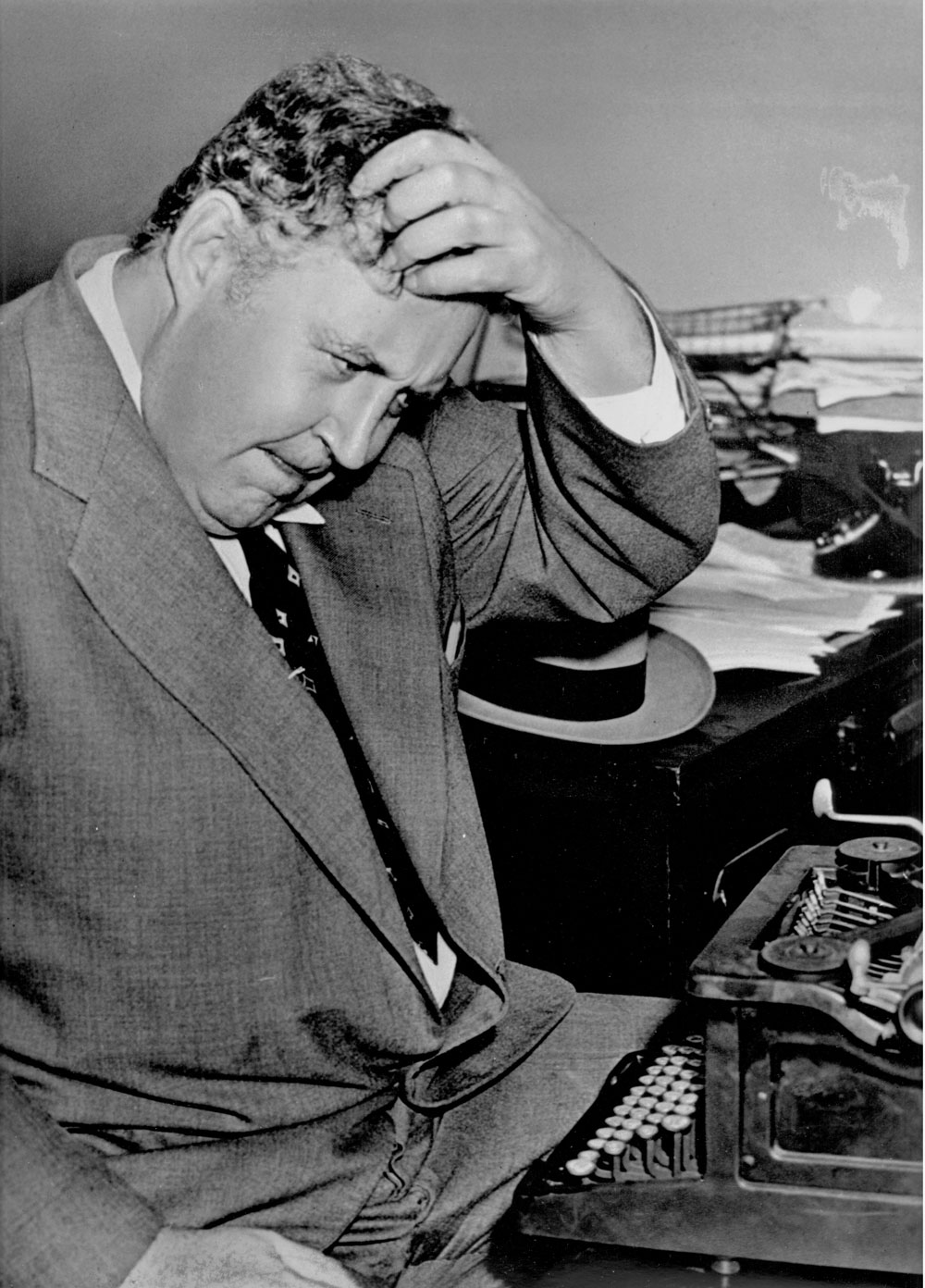

This column by Heywood Broun launched the Newspaper Guild. It was published in the New York World-Telegram on August 7, 1933, as well as in several other Scripps-Howard dailies. In the midst of the Great Depression, the unorganized white- and pink-collar employees of the newspaper industry were having their wages slashed, their hours increased and were being fired in great numbers — all in the name of economy.

Broun was one of the most successful, well-paid and respected newspaper writers of the time. He needed a union himself perhaps least of all, but could not stand by as thousands of other newspaper workers struggled for economic survival.

• • •

“You may have heard,” writes Reporter Unemployed, “that, although the newspapers are carrying the bulk of National Recovery Administration publicity, a number of publishers themselves are planning to cheat NRA re-employment aims.”“The newspaper publishers are toying with the idea of classifying their editorial staff as ‘professional men.’ Since NRA regulations do not cover professionals, newspapermen, therefore, would continue in many instances to work all hours of the day and any number of hours of the week.

“The average newspaperman probably works on an eight-hour day and six-day week basis. Obviously the publishers, by patting their fathead employees on the head and calling them ‘professional,’ hope to maintain this working week scale. And they’ll succeed, for the men who make up the editorial staffs of the country are peculiarly susceptible to such soothing classifications as ‘professionals,’ ‘journalists,’ ‘members of the fourth estate,’ ‘gentlemen of the press’ and other terms which have completely entranced them by falsely dignifying and glorifying them and their work.

“The men who make up the papers of this country would never look upon themselves as what they really are — hacks and white-collar slaves. Any attempt to unionize leg, re-write, desk or makeup men would be laughed to death by these editorial hacks themselves. Union? Why, that’s all right for dopes like printers, not for smart guys like newspapermen!

“Yes, and those ‘dopes,’ the printers, because their union, are getting on an average some 30 percent better than the smart fourth estaters. And not only that, but the printers, because of their union and because they don’t permit themselves to be called high-faluting names, will now benefit by the new NRA regulations and have a large number of their unemployed re-employed, while the ‘smart’ editorial department boys will continue to work forty-eight hours a week because they love to hear themselves referred to as ‘professionals’ and because they consider unionization as lowering their dignity.”

I think Mr. Unemployed’s point is well taken. I am not familiar with just what code newspaper publishers have adopted or may be about to adopt. But it will certainly be extremely damaging to the whole NRA movement if the hoopla and the ballyhoo (both very necessary functions) are to be carried on by agencies which have not lived up to the fullest spirit of the Recovery Act. Any such condition would poison the movement atFortunately columnists do not get fired very frequently. It has something to do with a certain inertia in most executives. They fall readily into the convenient conception that columnists are something like the weather. There they are, and nobody can do anything much about it. its very roots.

I am not saying this from the point of view of self-interest. No matter how short they make the working day, it will still be a good deal longer than the time required to complete this stint. And as far as the minimum wage goes, I have been assured by everybody I know that in the opinion all columnists are grossly overpaid. They have almost persuaded me.

After some four or five years of holding down the easiest job in the world I hate to see other newspapermen working too hard. It makes me feel self-conscious. It embarrasses me even more to think of newspapermen who are not working at all. Among this number are some of the best. I am not disposed to talk myself right out of a job, but if my boss does not know what he could get any one of forty or fifty men to pound out paragraphs at least as zippy and stimulating as these, then he is far less sagacious than I have occasionally assumed.

Fortunately columnists do not get fired very frequently. It has something to do with a certain inertia in most executives. They fall readily into the convenient conception that columnists are something like the weather. There they are, and nobody can do anything much about it. Of course, the editors hoping that some day it will be fair and warmer with brisk northerly gales. It never is, but the editor remains indulgent. And nothing happens to the columnist. At least, not up till now.

It is a little difficult for me, in spite of my radical leanings and training and yearnings, to accept wholeheartedly the conception of the boss and his wage slaves. All my very many bosses have been editors, and not a single Legree in the lot. Concerning every one of them it was possible to say, “Oh well, after all, he used to be a newspaperman once himself.”

But the fact that newspaper editors and owners are genial folk should hardly stand in the way of the organization of a newspaper writers’ union. There should be one.

Beginning at nine o’clock on the morning of October 1 I am going to do the best I can to help in getting one up. I think I could die happy on the opening day of the general strike if I had the privilege of watching Walter Lippmann heave a half a brick through a Tribune window at a non-union operative who had been called in to write the current Today and Tomorrow column on the gold standard.

—30—

While the Guild, as established at its founding convention on Dec. 15, 1933, limited itself to representing editorial employees, its 1935 Convention amended its constitution to state that one of the union’s purposes is “to promote industrial unionism in the newspaper industry.” Also at Broun’s urging, the 1937 Convention expanded the union’s jurisdiction to include all nonmechanical employees. And to the 1939 Convention, the last one he presided over before his death on Dec. 18 the same year, Broun said:

I feel the vitality of the American Newspaper Guild lies with the new people, the men and women coming in from the business offices, the circulation department and the advertising department. … Our strength is in broadening that base, in founding a good, solid, vertical, industrial union.

I would like to live to see it—that some day we will have ea union in newspapers in which we will have complete organization up and down the line, everybody in the city room, in the mechanical departments and in the business office, as well.

Editor’s note — This article is from the Newspaper Guild’s 80th anniversary book and is used with their permission.